Captain Zebulon Montgomery Pike was the first U.S. Army explorer to cross the present state of Kansas during his 1806-1807 expedition to the American Southwest, and was the harbinger of numerous military expeditions to follow. His primary mission successes, established for him by General James Wilkinson, were accomplished in other present states, such as the return of Osage Indians to their homes in western Missouri, a visit with Pawnee Indians in southern Nebraska, finding the source of the Arkansas River in Colorado, and seeking the elusive Texas source of the Red River. Pike provided the first published reports on Kansas and the Great Plains. His views of the region as a desert unfit for Anglo-American agriculture and best left to the American Indians affected the public image, although it also spurred the initiation of overland travel and commerce across Kansas and eventually opened trade between the Missouri Valley and northern Mexico that led to the development of the Santa Fe Trail.

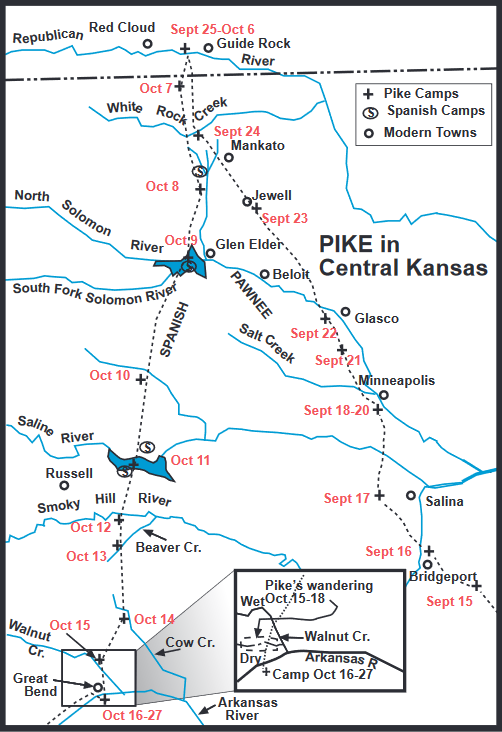

Pike’s command, including Lieutenant James B. Wilkinson, 19 enlisted men, interpreter Baronet Vasquez, a civilian physician, named Dr. John H. Robinson, and several Osages and Pawnees, entered present southeast Kansas on September 3, 1806, not far from what would later become Fort Scott. He had just completed his first major assignment from General Wilkinson, returning 51 Osages to their village in western Missouri. His next assignment from General Wilkinson was “to turn your attention to the accomplishment of a permanent peace between the Kanses and Osage nations.” As they guided Pike to the Pawnees, the Osages seemed fearful of meeting the Kansas. They crossed many rivers en route to the Pawnee village on the Republican River in present Nebraska, including the Little Osage, Neosho, Verdigris, Cottonwood, Smoky Hill, Saline, and Solomon, along with some of their tributaries. Soon after entering Kansas several of his Osage guides, fearing contact with the Kansas (enemies at the time), refused to go along and returned home. Those who continued with Pike took him on a long, circuitous route far to the west before heading north toward the Pawnees, thereby avoiding contact with Kansa hunting parties. At one point the Osages, thinking a Kansa raiding party was approaching, expressed great concern until the “party” turned out to be a running herd of buffalo.

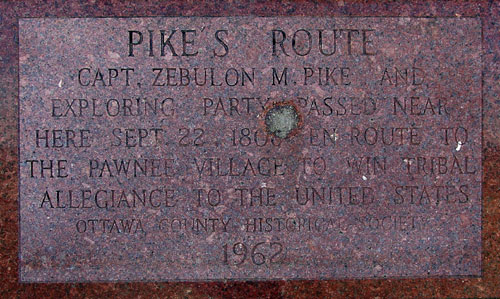

At the village of Republican Pawnees in present southern Nebraska, where Pike remained from September 25 to October 7, 1806, a delegation of Kansa Indians showed up and Pike brokered a peace agreement between the Kansas and Osages which became permanent. Pike also promoted peace between the Kansas and Pawnees, but that did not last.

Pike sought friendship and trade with the Pawnees, who were being courted by both the Spanish and Anglo-Americans but had made no firm commitments to either. The expedition faced a tense situation when he requested the Pawnees to lower the Spanish flag recently presented them by a large Spanish army detachment and raise the flag of the United States, but this was done. Pike also wisely told the Pawnees to keep the Spanish flag so they could hoist it if Spanish troops returned.

Pike requested help from the Pawnees, including guides and interpreters, so he could approach the Comanches farther west. As General Wilkinson explained to Pike, the Comanches, who were closely tied to New Spain (present Mexico), were considered the key to American expansion across the Great Plains. He told Pike “to bring the Camanches to a conference” and that “no pains must be spared to effect it.”

When he met with Comanche leaders, Pike was to “endeavor to make peace between that distant powerful nation, and the nations which inhabit the country between us and them, particularly the Osage; and finally you will endeavor to induce eight or ten of their distinguished chiefs, to make a visit to the seat of government.” Despite these orders, Pike never made contact with the Comanches, largely because the Pawnees considered them enemies and would not assist Pike, and he was unable to locate them on his own.

General Wilkinson considered Pike’s expedition a failure, in part, because he did not open relations with the Comaches. Wilkinson also considered Pike’s inability to find the source of the Red River —which eluded many later explorers—another sign of the expedition’s failure.

When the Pawnees were visited by 400 Spanish troops under Lieutenant Facundo Melgares a few weeks prior to Pike’s arrival at their village, they dissuaded Melgares from proceeding on to the Missouri River to attempt to find and arrest Lewis and Clark. Melgares had returned to Santa Fe. Now, at the request of Melgares and as an indication that they did not do the bidding of any other nation, the Pawnee leaders tried but failed to stop Pike’s push on southwest to meet the Comanches and find the source of the Arkansas River. Pike declared his men would fight to the last if the Pawnees tried to stop them. It was a precarious situation, but eventually the Pawnees permitted Pike to go on unmolested, and he headed back into Kansas to follow the route of Melgares to the Arkansas River.

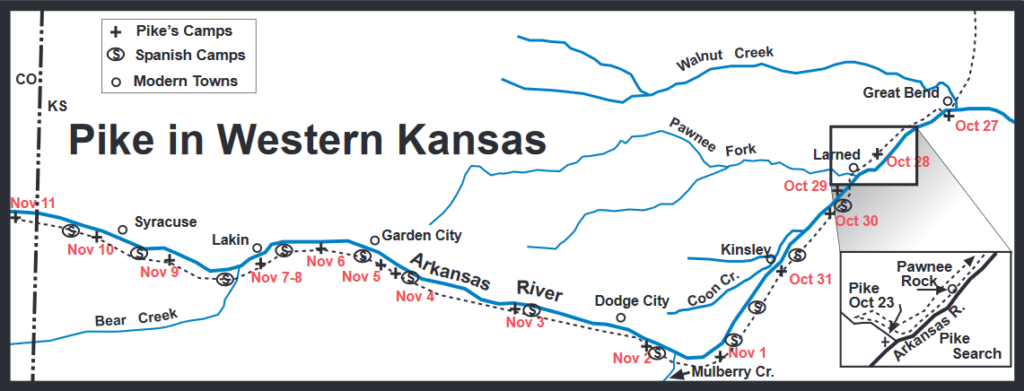

On the Arkansas, Pike sent Lieutenant Wilkinson, five soldiers, and two Osages on a descent of the Arkansas River in two canoes from near present Great Bend on October 28, 1806. Navigation proved impossible, and they soon abandoned the canoes. After hiking a week, they built new canoes and set out to navigate the river again. They faced many hardships and were “rescued” by a band of Osage Indians, who helped them to safety. They later navigated the lower Arkansas River and arrived at Arkansas Post on January 9, 1807. Pike and his remaining command continued westward along the Arkansas, following the trail of the Lieutenant Melgares and his 600 Spanish troops that preceded them by a few weeks. Pike later met Melgares and became friends with him in Chihuahua. From Melgares he learned much about crossing the Great Plains and about the people, geography, culture, and economy of northern New Spain, now Mexico.

Meanwhile Pike found the location of Melgares’s big camp on the Arkansas southwest of present Larned, where Melgares left a third of his army and most of the horses in camp while he and the remainder of his force pushed on to the Pawnee village. Pike, as noted, followed Melgares’s trace along the Arkansas into present Colorado. Along the way he recorded in his journal information about the herds of wild horses and buffalo. Pike noted his men had attempted to “crease” a wild stallion, one of the first recordings of this practice of shooting to stun a horse so it could be captured. The attempt failed. He noted the enormous size of the buffalo herds, declaring at one point that “the face of the prairie was covered with them, on each side of the river; their numbers exceeded imagination.” The troops feasted well on buffalo meat, but Pike forbade his men to wantonly slaughter the animals for the sport of it.

What Pike recorded about Kansas, comparing it to a desert, affected U.S. policy for years to come. The area became a dumping ground for eastern Indian tribes, and Kansas (and Nebraska) did not become a territory open to settlement until 1854. On the other hand, the information he gathered about crossing the Great Plains and about the region of northern New Spain (Mexico) on his expedition was published in 1810, and it stimulated attempts to open trade between the U.S. and northern Mexico and led to the opening of the Santa Fe Trail, the major portion of which crossed Kansas, in 1821. Pike set in motion a series of events that eventually led to the United States acquiring more than half of Mexico, including all or a portion of nine present states.

Pike followed Melgares’s route along the Arkansas River westward and, on November 11, 1806, out of present Kansas into present Colorado (which was actually once a part of Kansas Territory from 1854-1861). There Pike would soon sight the mountain which he called the Grand Peak, but which was later named Pikes Peak in his honor. He set out to climb that peak and then continued his search for the source of the Arkansas River. The weather was turning increasingly chilly, and their summer uniforms were feeling much more threadbare and thin as they forged ever westward toward the Rocky Mountains and the coming winter.

![Introducing the General Zebulon Montgomery Pike INTERNational Historic Trail [ZPIT]](../../../../wp-content/uploads/2018/07/21-St-Anthony-Falls-144dpi-wm-150x150.jpg)